By Roberto Alejandro, Editor-in-Chief

Early on in the State’s presentation of their case against Baltimore Police Officer William Porter in the death of Freddie Gray, prosecutors called Officer Alice Carson-Johnson to testify regarding the training Porter received in the area of law enforcement emergency medical care.

Carson-Johnson, an instructor at Baltimore’s police academy, and an officer with extensive field experience as a medic in both the military and police department, explained the training she gave Porter at the academy over the course of three days—out of a total academy duration of six months. Carson-Johnson would later describe that six month course as rigorous “to a point,” while under cross-examination by defense attorney Joseph Murtha.

But one of the most significant aspects of Carson-Johnson’s testimony was her contention that officer safety is “paramount” and that it is always the first priority in any emergency situation. She described the rationale for this contention: police officers are there to help others, and you cannot help anyone if you are hurt.

Special Agent John Bilheimer, another instructor for the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) responsible for training officers in defensive driving and emergency vehicle operation (a course that takes up three hours out of six months at the academy), testified that an officer is not permitted to transport detainees in patrol cars lacking a built in cage that separates the front passengers from the rear if the officer is by herself due to officer safety concerns. Defense witness Officer Mark Gladhill also testified over the course of the trial that officers seatbelt detainees being transported in patrol cars out of concern for officer safety (note: not principally out of concern for the safety of the detainee).

Porter, testifying in his own defense, spoke of officer safety as “paramount,” explaining that police protect life and property, but that before ‘property’ is ‘life’ (though, in this telling, ‘life’ seemed to mean ‘officer life’), and that every shift roll call ends with the admonition: “Back each other up.”

In describing why he never seatbelted Gray in the police transport wagon on Apr. 12, 2015, the day Gray was arrested, Porter claimed that he was concerned about the safety implications of attempting to seatbelt a man in a confined space—the prisoner transport compartment of a police wagon—while carrying a firearm, a weapon which an officer brings into every situation, and one which creates an “ever present danger” for the officer herself. According to Porter, there is never a time he is not concerned about his gun.

Chief Timothy Longo Sr., an expert defense witness in the area of generally accepted policing practices, testified regarding the objective reasonableness (a term of art meaning something akin to ‘justified’) of Porter’s actions on Apr. 12. Longo described police officers in the field as “always in danger,” and argued that Porter’s decision not to seatbelt Gray was objectively reasonable in light of the danger presented by the combination of a tight space in the back of the wagon and the firearm on Porter’s hip. It did not matter that Gray’s hands were cuffed behind his back, nor that Porter had already entered the van to lift Gray off the floor and move him to the bench, because the level of danger in any given situation can change immediately.

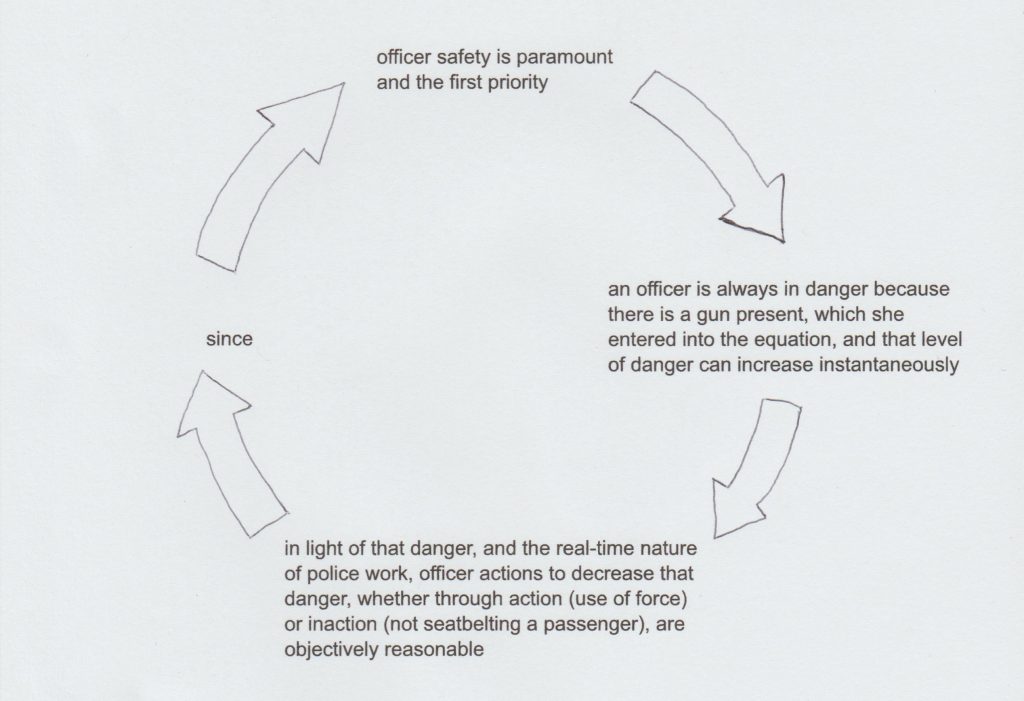

But here we have encountered a troubling circularity in the logic of police safety, especially where justifiable use of force is concerned:

This logic would seem to render almost any action by an officer reasonable, since the officer’s own gun is the source of her lack of safety. When the level of danger can shift at any moment, and an officer is already always in danger, forceful (over?)reaction seems all but guaranteed. And, according to this logic, impossible to second-guess.

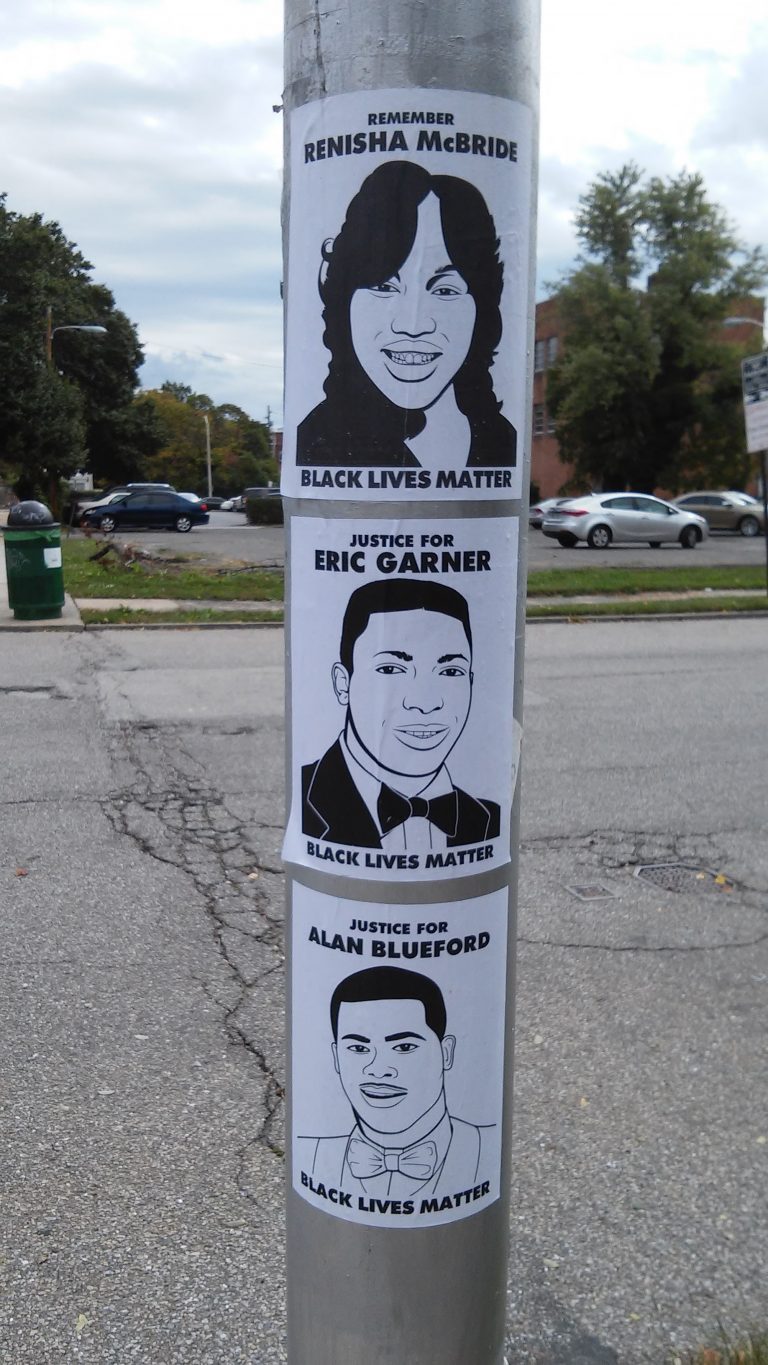

But of course, we know that not every dangerous situation in which police officers are involved ends in force, and that race often plays a big role in which incidents do (to wit, here are eight examples). It is clear that this logic, then, does not necessarily lead to constant uses of force. But, assuming one accepts the logic (a question presently before the jurors in this trial), it does seem to provide an instant justification for almost any officer action, and one that is hard to assail in light of the fact that the officer is not only always in danger because of her gun, but because the level of that danger can shift instantly (though this shift seems largely possible only in the direction of heightening the danger).

And this makes Carson-Johnson’s testimony all the more central to the Porter trial, because it not only sheds light on this problematic logic (at least if you do not think all police actions are always justified), but also highlights the relative lack of training officers receive before being sent out into the world to protect life and property. Should not an officer, often the first responder on a scene where medical aid might be necessary, receive more than three days of training on emergency medical care, especially if protecting life is the apparent priority of law enforcement?

Officers Porter, Matthew Wood, and Zachary Novak, all defense witnesses, have testified to a general lack of awareness of the Department’s General Orders, particularly where seatbelting detainees is concerned. Captain Justin Reynolds of the Baltimore Police Department, called by the defense as another police expert, testified on cross-examination that officers are expected to familiarize themselves with the General Orders and adhere to them as resolutely as possible. But he also said that there are around 1518 pages worth of orders, making it a difficult task.

But a six month academy training course is nowhere near long enough to teach even a significant percentage of those orders, not to mention everything else (like emergency medical care) that officers need to know. Couple that with what was stated by Captain Martin Bartness of the BPD, witness for the State, that a four person section in the Department oversees the compliance with general orders of almost 3,000 officers, and adherence to the regulations that are supposed to govern police behavior in the streets begins to seem less an aspiration than an impossibility. Bartness also claimed that the command ranks (captain and above) are additionally responsible for ensuring compliance with the General Orders, but, assuming the command ranks rely on supervisory ranks like lieutenant and sergeant for this task, there seem to be some hitches in this compliance model. After all, on the day Gray was arrested, the lieutenant on duty was patrolling the streets of the Western District on a bicycle, a district which Novak claimed is understaffed “90 percent of the time,” possibly necessitating the principal supervisor to patrol rather than supervise matters like compliance with rules and regulations.

The Baltimore Police Department, in spending relatively little time preparing its officers for a difficult and dangerous job, has effectively guaranteed a force generally unaware of the rules they ostensibly operate under. Couple that with a police culture that holds that officer safety is paramount AND that officers, just by suiting up, are always in danger, deviations from protocol that could prove fatal for the public start to feel inevitable.

It does not help that our laws contribute to the danger officers face. Porter, while on the stand, described his first arrest. He and another officer chased after a suspect who ran into a home, where Porter and the other officer managed to wrestle the suspect down before subduing him. What necessitated this chase of an unknown person into an unfamiliar and enclosed area for the officers? Possession of marijuana.

Our laws demand that officers take at times disproportionate risks, the Baltimore Police Department does not spend much time training these officers on the rules that govern their conduct, and the culture of policing—here the things police seem to repeat to each other on a regular basis—holds that an officer’s safety is paramount and always compromised.

These factors, structural in nature, did not combine well for Gray, who lost his life, in part, as a result of them. The other part that lead to Gray’s death is largely informed by the question of the personal responsibility for their actions of the officers involved in the arrest and transport of Gray on Apr. 12. Only the latter part is at issue in the trial of William Porter, though the former is implicated throughout. But if the only justice for Gray is the censure of six or some other number of officers, the trials will have served to validate a problematic system, not alter it.

This column was originally published by OnBckgrnd.com, on Dec. 13, 2015, under the title, “The Troubling Logic of Law Enforcement on Display in Porter Trial”.